A Charge to the Clergy By

the Rt. Rev. William Ingraham Kip

First Bishop of California,

A.D. 1876

My Brethren of the clergy,

The spirit and direction of the age are ever-altering, and our religion takes the hue and color of the intellectual spirit of the times. As, therefore, years flow on and the world changes, the impression of that change is stamped even upon the religious character of those who bear the Christian name. Thus every passing century brings with it some new form of error to be combated — some new assailant of our faith, whose attack must be met; and none can live well the Christian life without thoughtfully looking out on the world around and reading the “signs of the times,”1Matthew 24:3-31 to see what influences are acting on the spirit of our faith.

And especially is this the duty of those who are called to be leaders in “the sacramental host of God’s elect.”2likely quoting Charles Spurgeon They are to guide the struggling multitudes who are wandering in the wilderness—to point out the way over the Desert — and to warn against dangers which would cut them off from the Promised Land. And as the struggle goes on and darkness seems to gather about, from those who crowd the thoroughfares of life comes often the inquiry: “Watchman, what of the night?”3Isaiah 21:11

It is one which, as ministers of Christ, we should be prepared to answer. We should be able, from the development of the times in which we live, to gather the wisdom by which we may direct others in their warfare. The subject, then, which I would bring before you is — the Cʜᴀʀᴀᴄᴛᴇʀɪsᴛɪᴄs ᴏғ ᴛʜɪs Pʀᴇsᴇɴᴛ Aɢᴇ.

We might, in considering this subject, look at the centuries which have gone, and see how this principle was prominent since man first came forth from Eden, ever-changing its direction, yet ever exerting its influence. For instance, in the antediluvian times, when life was counted by centuries, worldliness was the prevailing difficulty. Men gave themselves up to pleasure and sensuality. Then came the days of the patriarchs, when idolatry was the besetting sin. Surrounded by heathen nations, they were tempted to yield to the old Chaldean superstition and worship “the moon, walking in brightness,”4Job 31:26 and the stars, night after night holding on their way amid the unclouded glory of that Eastern sky. A few centuries later, and, under the Jewish dispensation, the difficulty was formality, as, resting in a mere round of outward services, the Israelite forgot that these were but types and shadows, intended to prepare him for brighter and loftier revelations. With the dawning of the Gospel came a new order of things, as the old landmarks were swept away. In “the great trial of affliction”52 Corinthians 8:2 which befell the infant Church the members of the new faith were tempted to lose sight of earth, forgetting that here also they had appropriate duties to perform. With the triumph of Christianity, the danger arose from a different quarter. The Church attempted to adopt the varied ceremonies of the idolatry it had vanquished, and through the Middle Ages superstition paralyzed its strength. But, since the Reformation, the evil has been exactly the opposite. A questioning intellectual religion, which chills devotion, has replaced that abounding faith which “believeth all things.”61 Corinthians 13:7

But time forbids that I should enter more fully into this historical review. I allude to it only to show that the human mind is prone to extremes, and external circumstances of course determine the direction it shall take. But you perceive how this truth comes to us through the mists of time. The Christian, indeed, cannot sever himself from the past; for thence, in solemn strains from its far-distant ages v float down to him the noblest lessons he can learn. In the things which have been, he reads his prophecies of the things which shall be.

“And as King Saul

Called up the buried prophet from his grave

To speak his doom, so may the Christian now

Call up the dead past from its awful grave

To tell him of our future.”7An adaptation of a stanza taken from Alexander Smith’s A Life-Drama

Let us look, then, at some of the characteristics of our own age, particularly as they most concern those whose appointed duty it is to act upon the minds and souls of men.

The first I would mention is the tendency to mistake mere civilization of mind for religion. Our faith has silently produced an entire revolution in the state of feeling which pervades society. In the ages in which it first appeared even the ordinary amusements and the intercourse of daily life were characterized by what, in this day, we should call a revolting barbarism. The Christians became, therefore, at once a marked and separate people. They alone would not frequent the amphitheater, to join in its ferocious sports, and they alone could derive no pleasure from the gladiator’s show, where man died in agony by the hand of his fellow-man —

“Butchered to make a Roman holiday.”8Lord Byron, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, Canto IV

As Christianity advanced, this refining and humanizing influence extended until it pervaded the masses of men, sweeping away this barbarous spirit, and now whole communities enjoy the benefits it has spread around, without even thinking of the source from which they proceed. The exterior surface and polish which society at this present-day exhibits is much in accordance with what the Gospel would produce; but the difference is, that instead of being the result of the direct personal influence of religion, it proceeds only from education.

The reason now is cultivated, the taste formed, and refinement and grace are spread over the face of society. In our ordinary intercourse, a delicacy has been introduced which contributes to social order and domestic comfort, and prevents any exhibition of violence or passion. Our relative duties, therefore, are carefully performed, and open vice is stigmatized as unseemly and out of taste. Profligacy is discountenanced, and all actions violently at war with our sense of propriety are esteemed a disgrace. This is the external view which society presents at the present time.

Now, how many thousands can you see about you, living under this state of things, who, in consequence, consider themselves Christians! They believe that their general tastes and habits are those which are prescribed by our faith, and with this they are satisfied. They are kind, perhaps, and charitable, from natural disposition, or because the world pronounces these traits to be reputable. And if, in addition to this, they engraft religion formally on their system, it also partakes of the worldliness in which they live. They only adopt from it whatever commends itself to them as being refined in sentiment and in accordance with their own views. They desire to have their feelings alternately aroused and soothed by the scenes which it arrays before them. They, therefore, call themselves by that holy name which first the disciples assumed at Antioch, and as far as our faith agrees with the tone of the society in which they live, they yield to it an outward obedience.

Yet what is all this but a mere counterfeit of the truth, dressed out to imitate it by the enemy of man, that he may deceive many? He comes as an angel of light, presenting a system built on worldly principles, yet pretending to be the Gospel. The peculiarities of former generations have passed away, a new order of things has taken their place, and this is claimed to be an exhibition of Christian character. And is not this the only faith to which many in the world about us can lay claim — a faith which has no true fear of God—no fervent zeal for His honor—no jealous adherence to doctrinal truth—no self-denial for Christ’s sake? And would the whole tenor of their lives be any different if the Gospel should now be proved to be a fable? What is this, then, but mere civilization of mind—an effect which the high polish of society might produce on any individual who had never heard of the Gospel? It is a beautiful development of character, but one which might take place under heathen influences. There is nothing about it distinctly Christian.

“They cherish every grace

Except the cross — except the strenuous race.”9The Rt. Rev. George Burgess, D.D., The Strife of Brothers, Part I.

Again: another characteristic of the age is an indifference to the value of religious truth —a false liberality, which induces men to tolerate error, when it should be shunned and denounced — a charity which degenerates into weakness.

This is a fault peculiar to our age, and which has had its growth in the last two centuries. It was not so in the early Church, for then the rule was: “Prove all things; hold fast that which is good.”101 Thessalonians 5:21 It was not so in the ages which succeeded, for then the Church, fallen as it may have been from the purity of the faith, was still zealous to defend the truth, or what it believed to be the truth. Neither was it so in the times which immediately followed the Reformation. Then the great contests and disputes which had taken place impressed on the world the fact that the truth was something to be sought after; and, when found, they were willing to cleave to it with full purpose of heart, even at the cost of life itself.

But, since then, days of peace and quiet have come upon us. We forget how much those who have gone before us suffered because they would not subscribe to error, and we learn to prize but little those principles of eternal and immutable truth to which they were faithful, even unto death. We look with a mild and lenient eye upon those who have perverted it, until we ourselves begin to undervalue its possession; and thus our Lord may well complain of us as being deficient in the jealous custody of that word which He revealed. He may say of us, as of the Jews in Jeremiah’s day: “ They are not valiant for the truth upon the earth.”11Jeremiah 9:3

Now, brethren, the truth is but one. It cannot have two forms or two appearances; and, of all truths, the most precious are those which relate to our religion. Does it become us, then, on such solemn and momentous subjects, to join in with the false liberality or the misnamed charity of the day, and assert that an individual’s sentiments on these topics are matters of secondary importance, or that “ no man is responsible for his belief? ”

We often do this, not from worldliness or cowardice, but from personal attachment to the individuals, from a desire not to disturb the feelings of others, or because we look upon their errors only as speculative opinions, of whose dangerous tendency we are ignorant. Thus we hear one scoffing at the punishment of the lost, and proclaiming that all shall alike be admitted into Heaven, and we feel no horror at his rejection of the plain truths of revelation. We listen to another while he denies the Divinity of our Lord, and thus strikes a death-blow to the whole Christian scheme, and we shrink not back from a heresy the mere announcement of which would have aroused the indignation of those apostles, to whom their Master’s memory and love were precious.

But such lenity is very far from being that which Scripture inculcates on this subject. St. Paul, after enumerating the long catalog of heretics who should arise in “the last days,” adds, “From such turn away.”122 Timothy 3:5 And St. John is still more explicit. After speaking of those who “abide in the doctrine of Christ,” he says, “If there come any unto you and bring not this doctrine” — what were they to do? Give him the right hand of fellowship? Close their eyes to his heresy for charity’s sake? No. The apostle says: “Receive him not into your house, neither bid him Godspeed; for he that biddeth him Godspeed is a partaker in his evil deeds.”132 John 1:7-11

And I would speak particularly of this apostle, because those who are remiss in the faith ever represent him as being filled with the love of all men, and pretend to shelter themselves beneath his example. It is true that this was one part of his character, but yet, you perceive, there was another light in which we may see him exhibited. The warmth of his charity never interfered with his love for the souls about him or his zeal for the truth of God. He loved men, but he “loved them in the truth,” and “for the truth’s sake which dwelleth in them.”142 John 1:1-2 Yet he could denounce those who denied the faith or turned away from the teaching of that Church which his Lord had made “the pillar and ground of the truth.”151 Timothy 3:15 While, therefore, our associations with the beloved apostle are those of charity and love—while we remember that his single exhortation to the Church at Ephesus was, “Little children, love one another!”16This is a story from Patristic Tradition:

The blessed John the Evangelist lived in Ephesus until extreme old age. His disciples could barely carry him to church and he could not muster the voice to speak many words. During individual gatherings he usually said nothing but, “Little children, love one another.” The disciples and brothers in attendance, annoyed because they always heard the same words, finally said, “Teacher, why do you always say this?” He replied with a line worthy of John: “Because it is the Lord’s commandment and if it alone is kept, it is sufficient.”

–St. Jerome, Commentary on Galatians, 6:10—let us not forget that he it is who bids us hold no fellowship with those who reject the truth.17See Newman’s Sermon Tolerance of Religious Error

But is not this a very different spirit from that which prevails in our day and generation? Yes; we have with us an unmeaning benevolence, which we misname Christian love. The Church needs a holy zeal—a sternness for the right—a determination, at all hazards, to maintain the truth. Never, indeed, will purity of faith be valued until we shrink not from proclaiming, openly and boldly, our censure of religious error, whatever may be its nature. Never will the Church regain its power until its followers, “ quitting themselves like men,”181 Samuel 4:9, 1 Corinthians 16:13 adopt a stricter discipline — look less leniently on the faults of those who have departed from it—and show that their love is united with firmness, strictness, and boldness. Then, at length, will men begin to feel that there is some value in the truth.

Again: We turn to another development of the times. This is an age of irreverence. In “our fathers’ days, and in the old time before them,”19Possibly a reference to the Pulpit Commentary on Joshiah 4:1-24. It seems to have been a common expression in the 19th Century and can be found in homilies by both Spurgeon and Neale. society was characterized by a reverential spirit. There was then something to be looked up to, while the present generation, in its pride of self-sufficiency, seems to regard nothing.

For instance; old age was once held in reverence. Men recognized the fact that the dignity of age surpasseth all other dignities. They felt that one who had lived many years had a long experience on which to look back, and was also drawing near to the solemnities of the coming world. The small space which separated him from those fearful secrets which the living desire to read, yet shrink from knowing, invested him with a dignity which in earlier life he had never possessed. So it has been through all ages, and men everywhere united in acknowledging that “ the hoary head is a crown of glory.”20Proverbs 16:31

But how little of this spirit do we now see! As the young rush into busy life they will not listen to the voice of those to whom “length of days is understanding.”21Job 12:12 In their hot and hasty pursuit the aged are elbowed from their path. They are rather regarded as cumberers of the ground, and their warnings received with mocking laughter, as the words of those who are far behind the spirit of the age. Even the exhibitions of outward deference which characterized former generations are gone, and in the struggle for this world’s prizes none pause to obey the injunction of Scripture: “Thou shalt rise up before the hoary head and honor the face of the old man.”22Leviticus 19:32 We have indeed upon us the curse which was denounced against ancient Judah, that “The child shall behave himself proudly against the ancient.”23Isaiah 3:5

And so it is in matters of much higher moment. There is a decay in the spirit of reverence with which all sacred things are regarded. The leveling political spirit which is abroad in the world has extended its influence to the Church. Its sacred offices are looked upon by men as they would upon any kind of secular business, and “they which minister about holy things” are treated as if they were merely appointed for the intellectual gratification of their hearers, or, far worse, as “hirelings who are to accomplish their day.”24Job 14:6 There is a total forgetfulness of the authority of their office — that they are God’s ambassadors to stand between Him and His rebellious subjects— that they are (to use the words of the apostle) “in Christ’s stead.”252 Corinthians 5:20 The command of St. Paul is disregarded, to “Esteem them very highly in love for their work’s sake.”262 Thessalonians 5:13 The flock remembers not that these are their shepherds appointed by God, nor do they carry out the description of our Lord: “The sheep hear his voice; he goeth before them, and the sheep follow him; for they know his voice.”27John 10:3-4 Thus it is that the interests of religion suffer, because they who profess to bow to its precepts in their worldliness drag down the authority and degrade the dignity of those who are its appointed teachers.

And — to go one step farther — look at the manner in which the most hallowed mysteries of our faith are treated. Themes which, ages ago, would have been spoken of only with awe, are now flung from lip to lip and debated with a recklessness which strips them of all appearance of sanctity. The sacred subjects of Holy Writ and its inspired words are used to point a jest, until there are remaining no solemn associations with language which prophets and apostles used of old, when they were “moved by the Holy Ghost.”282 Peter 1:21

Is not this, brethren, a sorrowful but true picture of one phase of the times? Have we gained as much by the “progress of the world” as in our pride we are accustomed to believe? While we have freed ourselves from many of the errors of the Middle Ages, have we not lost also many of their virtues? It is doubtful, to say the least, whether an age of superstition is not preferable to one of irreverence.

The next ‘sign of the times’ to which we would refer is the natural development of those we have already mentioned. This is an age of increasing infidelity. When truth ceases to be valued, and a reverence for all holy things is passing away, what can we expect but that skepticism should abound? Unbelief in this day is assuming a new form. A century ago it was confined to the thinking and the intellectual. In the quiet of their studies men reasoned on the great verities of our faith, but it was for themselves and the narrow circle which was like-minded with them. And if Hume, and Herbert, and Bolingbroke sent forth their views through the Press, it was to the same audience that they appealed. The mighty masses of men were unaffected. They had inherited the truths of our faith, and with little, perhaps, in this world to cast sunshine on their path, they clung more closely to the promises of another life, and looked forward with earnest longing to their entrance on that state where “the weary are at rest.”29Job 3:17

But now, infidelity is no longer confined to the study or the seat of science. Education has elevated the masses, and, for good or evil, prepared them to hold communion with the loftiest minds in the world of thought. The children on the benches of the school, or the artisan at his toil, are able to “read, mark, and inwardly digest” subjects which were far beyond the wisdom of their forefathers.

There has been created, too, what we call ‘the reading public,’ and a mighty audience has been formed, of which, centuries ago, scholars knew nothing. The Press scatters everything broadcast over the earth, and who can say that its teachings, in most cases, do anything but mislead the intellect and debase the heart?

Thus it is that the ignorant and the half-learned are puffed up by the pride of self-knowledge, and in the shallowness of their wisdom are induced to abandon the truths in which their fathers trusted.

And how often is this the case now, even with the thoughtful and the cultivated! It is esteemed a proof of intellectual freedom to disown the facts of revelation and to regard the teachings of Scripture as “cunningly-devised fables,”302 Peter 1:16 which the world has outgrown. And then, too, there is a spirit of skeptical philosophy abroad which induces men to accept anything sooner than the Gospel. No theory can be too wild to enlist followers or too improbable to gather converts. And now, in these ‘latter days,’ when time in its solemn march is each year bringing forth new proofs of the historical facts of our faith — when the hieroglyphics of Egypt and the tablets of Nineveh are contributing their arguments to confirm all that the prophets and sacred penmen have written—’a generation wise in their own eyes’ can turn from them, to yield their belief to the original “developments” of Darwin or the glaring impostures of spiritualism.

Yet so it is, brethren, around us. We bear it on every side. Our feelings are shocked by the bold blasphemies which are announced before the world, and the degraded morality which would well have become the Cities of the Plain on the day that the storm of God’s wrath burst upon them. We recognize the results of this infidelity in the recklessness with which men turn away from the temple of God, or, should they enter, in the chilling apathy with which they listen to truths before which the holy and the good of ages past have bowed in reverence.

We will consider but one more development of the age; but it is one which, more than any other, meets us in this land in which our lot is cast. This is an age given up to the worship of Mammon. It is not only an age devoted to the attainment of physical benefits, but the pursuit is carried on with an intense excitement, where all are swept onward by a wild and headlong current. The whole society with which we are brought in contact is marked by an activity of thought which, we believe, the world has never before witnessed. It rests not day nor night. Every mind — often in spite of its own better resolutions—catches this restless spirit, and it is embodied in a thousand schemes which the calm decisions of reason cannot indorse. The past to which in this land we can look back is scarcely long enough to bring to us the lessons of experience. A nation has been born in a day, and, hardly pausing to enjoy what the passing hour offers, all are urging forward to some beckoning promise in the future. The imagination of each one is dazzled, and he rushes forth to take his part in the conflict, where enterprise, adventure, and ambition are hurrying all forward. There is no repose, no pause in the race, but every languid muscle is braced to vigorous exertion and every mind is awakened to its highest exercise.

The question, then, is, what direction is all this excited intellect to take? Unfortunately for us, this multitude, which is thus awakened to such earnest effort, is agitated by the ceaseless grasping after gain. The love of wealth, which in other ages has held an important place in the human heart, seems, in these last few years, to have increased, until there is danger lest it absorb all other feelings and reign sole master in the breast.

In other lands there have been checks to this inordinate growth of avarice, which substituted other objects of reverence for that absorbing love of money which characterizes us as a people. There was, for instance, a reverence for ancient institutions and long-established forms. There was the pride of ancestry, which called men to walk worthy of their fathers’ fame, and not, by their failures, erase the inscriptions of honest praise which were graven on the monuments of those who had gone before them. There was, too, a higher estimate of intellectual and moral worth. Men bowed to the supremacy of genius, and acknowledged that mind was more elevated than matter — that he whose radiant spirit seemed lighted up by the God of Heaven, and gifted with strength to exert an influence on all around him, possessed a treasure more to be envied than if he had been master of countless stores of this world’s gold. Then self-denial and devotion were living things — patriotism and loyalty were active principles — and the worship of Mammon had not yet shriveled up the souls of men into self-seeking and sordid pride. But many of these high and ennobling considerations have, with us, faded away, and we are living in a generation which seems to have no reverence for anything but money. ‘The greed of gold’ in this land is absorbing every other feeling. The Polytheism of the ancient world indeed is gone, but it has given place to the worship of a god whom Milton describes as:

— “the least erected spirit that fell

From heaven; for e’en in heaven his looks and thoughts

Were always downward bent, admiring more

The riches- of heav’n’s pavement — trodden gold —

Than aught divine or holy else enjoyed

In vision beatific.”31John Milton, Paradise Lost

We might speak of the injurious effect produced upon the tone and spirit of society by the prevalence of these feelings. The poetry and romance which once invested life have given place to the claims of mere utility. The sentiments which in former days refined and ennobled society are considered antiquated. The lofty tone of honor, once so highly prized, has deteriorated; the refinement which pervaded society has diminished, and its morality has been gradually sinking to a lower ebb. In the excitement produced through our land by the acquisition of.sud- den fortunes, strict and stern integrity has been forgotten, and men mount up to wealth by greed and wrong, which should draw upon them the withering scorn of all who value honesty and right. But society is learning to call such things by soft and lenient names. Wealth covers a multitude of sins, and the voice is but feebly heard which should rebuke this prevailing idolatry of wealth. The physical resources of our land, thrown open to everyone who has the zeal and heart to labor, hold out the promise of a golden prize to all, and few are there who have strength to turn away from the multitude who are groveling in the dust—few who can rest in the conviction that there is something more valuable than money, and the search after which is more dignified for an immortal spirit. We seem, in this land, to have realized the ancient classic fable of Midas, turning everything he touched to gold; but cannot we conceive of a more lofty character for a nation than that its god should be Mammon and its temple the Exchange?

But it is becoming the general impression that the acquisition of wealth is the most important business of life, and that he is best fitted for intercourse with the world who possesses most sagacity in heaping up riches. Even political office has lost its value, and is cared for only for the emoluments it brings. To purify the heart and humanize the affections — to provide, not only the means of elevation in life, but the ability to bear success with propriety—to confer, not the power of subduing others, but the means of conquering one’s self—to impress all those solemn lessons, which alone can guide man in his warfare, and which lead him to look to a life beyond life—all these are passed by unheeded by the giddy multitude around us. Thus, in the rising generation is created an intense and feverish attention to worldly objects, while they are scarcely taught that the deepest of all mysteries into which we can penetrate is the human heart, and the highest improvement would be the eradication of one sinful passion or the extinguishing one guilty propensity in that dark fountain of evil. Thus the mind is taught to look only to the Material and the Earthly, and soon has no sympathy with the True and the Spiritual.

But beyond all this influence on this world, how utterly destructive is this spirit to the religious character! How impossible does it seem to unclasp the hands which are madly clutching at gold, or to find room for Christ and His gospel in hearts where Mammon is already enthroned! Three thousand years ago the wise man declared: “He that maketh haste to be rich shall not be innocent;”32Proverbs 28:20 and now we have around us, on all sides, evidences that the flight of centuries has not changed this law of life. We read it in the apathy to the Gospel of these toilers after wealth, with regard to whom the command might well be issued: “They are joined to their idols; let them alone.”33Hosea 4:17 We see it in the wreck of Christian character which so often befalls those who come to these shores, and in the desperation which fills a suicide’s grave, when the god they have worshiped will not shower his gifts upon them.

Such, then, my brethren of the clergy, is the conflict in which we are engaged. Is it discouraging? Do we at times feel disposed to throw aside our weapons and exclaim that this is a weary strife, in which all our efforts are useless? Such feelings are unavoidable; but we must struggle against them, striving to follow in the steps of Him who, though He “went about doing good,”34Acts 10:38 was “despised and rejected of men.”35Isaiah 53:3 It is with our armor, worn and dinted in the conflict, that we must present ourselves before the Great Captain of our salvation. The struggle is ours — the result is with God.

“Great duties are before us, and great works ;

And, whether crowned or crownless, when we fall

It matters not, so as God’s will is done.”36Alexander Smith, A Life-Drama

Remember, then, that you are “citizens of no mean city,”37Acts 21:39 and must walk worthy of the name you bear. Freeing yourselves from all temporary and selfish ends, let the solemn results for which you labor cast their influence over every act and purpose. Unless you do this you will find yourself laboring in vain. The strength to wage the warfare will be paralyzed. In the mighty struggle which is Qmino; on you will “fight as one that beateth the air.”381 Corinthians 9:26 Unfitted for the ‘high endeavor’ to which you are called, your influence will be lost; and when you pass away it will not be recorded that you have done anything which shall be written in deep and solemn characters upon the souls of men.

But live the true life of the Christian soldier, as they have done who left the earth fragrant with their footsteps, and how noble the results you may produce! Everywhere your field will be around you, and your power may be felt. Not only in the hushed and solemn stillness of God’s temple can your voice be heard, but it can penetrate to the quiet circle which has gathered around ten thousand hearths through our land, and be listened to above the noise of the busy and toiling crowd. In the mart of traffic, where the merchant bargains — on the restless sea, where the weary sailor tosses — amid the turmoil of political strife — by the side of the husbandman, as he turns up the furrow, and of the artisan, as he plies his toil—where sorrow weeps and joy raises its note of exultation — everywhere that the spirit of man is struggling with temptation and sin, and poor Humanity is going through its trial—everywhere that the solemn mystery of this life is passing—may the Christian minister find his sphere of labor and influence.

With, then, my brethren, this wide-spread power, how are we using it? The pulpit is said to contain within itself ᴛʜᴇ ʟɪᴠɪɴɢ ᴘᴏᴡᴇʀ ᴏғ ʀᴇᴘʀᴏᴏғ. Are we bringing it to bear upon the crying sins of the age, proclaiming its warnings as fully to Dives in his hall as we would to Lazarus at his sate? Avoiding those harmless generalities which awaken no fear and arouse no murmurs of conscience, do we speak with the directness which brings home the pointed application, “Thou art the man!”392 Samuel 12:7 While the covetous and the frivolous are treading the ways of death, do we utter the startling rebukes which can awaken them from their dreams? While we are standing among the dying, and from our firesides and our pews they are gliding into eternity, do they hear anything from us to warn them of their coming doom? Does the commissioned herald of the Cross urge them to awake from their lethargy and flee to the City of Refuge; or does he seek to dazzle the mind when he should improve the heart, preaching himself instead of his Lord, striving, as it were, “ to carve his paltry name upon the rugged front of Christ’s own cross? ” Does he wave the censer between the living and the dead, that the plague may be stayed?40Numbers 16:48 Does he carry with him, through all his social intercourse, a Christian example, ever inculcating the lesson that this life is fast vanishing away, and that soon the judgment will be set and the books be opened and all assemble to have their accounts balanced for eternity?

These, my brethren of the clergy, are the inquiries which are naturally suggested to us by the subjects I have endeavored to bring before you. How fearful, then, the record which is going on against us, as we lead and follow our people to the grave! We are “set for the fall and rising again of many in Israel.”41Luke 2:34 If we are faithless, our garments will be dripping with the blood of the ruined and the lost. And soon for us all visible things will have passed away, and we stand up to have every action brought into review — the motive of every sermon analyzed — and the feelings examined with which “our eyes have seen and our hands have handled the word of life.” Realizing, then, our own entire weakness, let us cast ourselves upon Him who alone can give strength; and while we record our weeping penitence for the past, let us seek grace to labor as those who feel that a world around us is sinking into ruin, while above us are the opening heavens, to whose ‘tearless state’ we must invite those for whom Christ died and eternity is waiting.

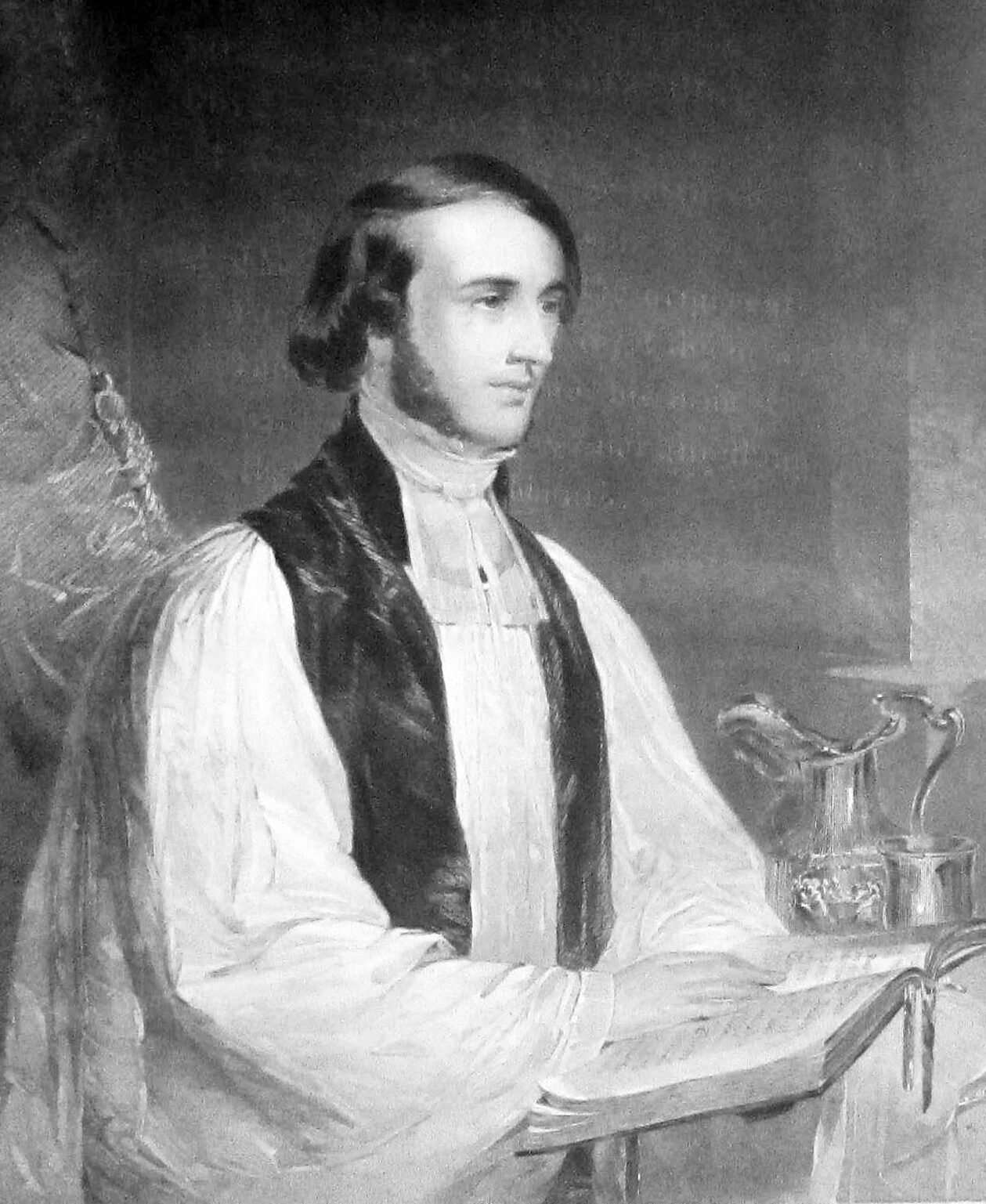

The Rt. Rev. William Ingraham Kip

Bishop William Kip was born in New York City on October 3rd, 1811, to Leonard and Maria Kip. He graduated from Yale in 1831, and the General Theological Seminary in 1835. He was ordained to the Diaconate and then Priesthood in the same year he graduated from the seminary. In 1853, he was selected to be the first Missionary Bishop to California and was consecrated to the Episcopate by Bl. Bishop Jackson Kemper, Bishop Alfred Lee (first Bishop of Delaware), and Bishop William Jones Boone (first Missionary Bishop to Shanghai). Kip served as Missionary Bishop to California for forty years until his death in 1893. Kip’s writing had a significant impact on the generation of Churchman immediately following his own. His robust work in defense of the Historical Episcopate, The Double Witness of the Church, served as the catalyst for the theological convictions and missionary zeal of none other than Bl. James Lloyd Breck, our our ‘Apostle of the Wilderness’ and founder of Nashotah House Theological Seminary.